That actually seems to be the point – too many for all the predators ensures that some will get below ground (sometimes conveniently buried there by forgetful squirrels), germinate, and become oak trees. What’s mysterious, and wonderful, is how nearly all the oak trees across the country choose the same year to over-produce.

Acorns are not merely a valuable food source for wildlife, however. Humans have used them for millennia. Dried, the kernels can be ground up and used as meal, or flour, although they are very bitter unless treated by repeated washing to sweeten them up. As this is clearly a bit of a faff, most mediaeval peasants and farmers used acorns to fatten a pig instead, and the pig clearly doesn’t have a sweet tooth. Remember Piglet in Winnie-the-Pooh and his Haycorns? Acorns were used widely, along with other plants such as chicory and dandelion roots, during the second world war, as a coffee substitute. The nuts have to be chopped well and roasted, then ground up and roasted again. They are actually not unlike coffee when made into a drink, but I confess I’m no coffee gourmet. The bitterness comes from tannin, which is found in most parts of the oak tree. Some tannin sharpens flavour (as in a cup of tea). It also has medicinal uses as an astringent, and ground acorns have been used in a tincture to treat chronic diarrhoea.

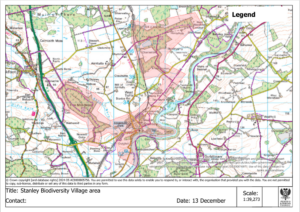

With woods in mind – especially woods where greater tree diversity would benefit the ecosystem – it seems only sensible to harvest some of this extraordinary acorn surplus and introduce the oaks-in-waiting to our woods. Neither Five Mile Wood nor Taymount Wood boast much in the way of oak trees, even though Kinclaven Bluebell Wood, right on the doorstep, is ancient oak woodland.

Why introduce oak trees? They live for hundreds of years and support the greatest variety of other species of any of our native trees. They continue to act as habitats, homes and food larders long after they are dead. And they’re outrageously lovely. Fungi interact with oak tree roots and give rise to soil conditions that are perfect for some iconic wildflowers (the bluebell is just one). They ring with birdsong in spring. They can be chewed and mined by a thousand invertebrates, yet scarcely seem to notice (but beware the dreaded Oak Processionary Moth). There are also good reasons for using acorns from a wide range of trees. Collecting from oak trees in varying habitats, big, small, spreading, upright, ensures genetic diversity, which is vital to all plants (and almost all animal species) for resilience to challenges from climate, predation, changes in habitat and so on. Local sources are good, because the trees producing mast have already self-selected for local conditions.

So West Stormont Woodland Group are going after acorns! Join us to collect mast from local woods now, and in the new year we’ll all go and plant them in Five Mile Wood. This wood’s been chosen because it has a large gap area to

repopulate, and because it’s ridiculously full of gorse. How does gorse help? It will protect the baby trees in the early years from deer, who just love a mouthful of sapling to chomp on. Planting should be easy – just a stick and an acorn in the hole. Squirrels manage it, so I’m sure WSWG will, too. Not every acorn will make a full grown tree– so let’s gather lots and lots. We won’t see them mature. But we can know a vision for the future, here and now.

Watch this beautiful acorn germinating underground and then the oak seedling growing. Time lapse filmed over 8 months!