I wonder what happened to One, Two, Three and Four Mile Woods?

But once through the gate at the end of the straight track, the going is tricky. At this time of year, wellies are essential, thanks to the legacy of ditches, boggy ground and waterlogging that followed the felling of the trees here. When did it become the norm for forestry practice to leave such a mess? However, with care, agility and thanks to the enterprising actions of previous walkers using felled timber to ford the worst ditches, you can get to the main path that circles the wood.

Deer, birds and other animals have their own paths off into the undergrowth, but for humans, the area where trees were felled before the Commission ceased to work are becoming impenetrable. Gorse crowds thickly on either side of the track, requiring constant maintenance to keep it from meeting in the middle. Self-seeded birch, larch, Scots pine and willow are all growing well, but there are no paths between them in this baby wood. Then there are the trackside deep ditches, another legacy of forest drainage operations, not impossible to cross but very off-putting.

So walkers, joggers and cyclists stick to the circular path and leave the wood by the way they came. Someone on Trip Advisor found the wood disappointing, and the circular track through felled forest boring.

But I wonder. We undervalue landscapes that aren’t “finished” – such as newly planted gardens and self- seeded woods at the start of succession. The prettiest part of Five Mile Wood may be the winding bike- track under mature trees which shoots off from the main path near the south entrance, but the burgeoning growth of pioneer vegetation in the centre – the “gap site” as some call it – is vibrant with hidden life, resounding with the flickering flight of small birds and bubbling with amphibians and aquatic life in the ponds and ditches created for drainage.

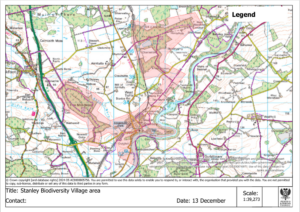

Even the nuisance gorse is a rich nectar source for pollinators and home, each bush, to thousands of spiders and other invertebrates. It’s not what we are schooled to believe beautiful, but in terms of ecology and resilience, it is every bit as valid as ancient oak climax woodland. Not all landscapes can be measured in human terms – though the amount of carbon sequestered by rapidly-growing trees and shrubs will be enormous and far greater than that in a carefully-planned, gardenesque setting. And humans need carbon sinks as much as every other life form. People like to have choices, though. Choices about where to enter the wood – entrance points close to all the settlements that lie within walking distance. New tracks to follow, new routes to explore, the chance to come out into the sunshine at a different point from where you went in. Paths that cross, diversions, sidetracks, viewpoints. I don’t think they should be the main focus of the wood, or dominate the richness of undisturbed wildlife in the centre. There must be places that are no-go areas for humans, where nature can get on with it, and prove, as ever, that she will make a better job of it than we can.

And then, let our tracks meet and link wood to wood, as we learn to walk more, and be more in nature and less apart from it. Then we will lose our expectations of park furniture and entertainment, and realise the woods aren’t, in the end, all about us.